Note: This article originally appeared in Modern Photography in 1987; I republished it in my web site, Black & White World. Unfortunately, that site is down for the foreseeable future, so I’m reposting it here as it is frequently referenced. My apologies for the inconvenience for those who have been having trouble finding this.

Coffee and Workprints:

My Street Photography Workshop With Garry Winogrand

Two weeks with a master of street photography and his street photography tips that changed my life. Here’s everything Garry Winogrand taught me about street photography.

By Mason Resnick

My two-week workshop with street photography pioneer Garry Winogrand began in a third floor classroom above crowded Nassau Street in lower Manhattan in August 1976. We spent the first day looking at his portfolio.

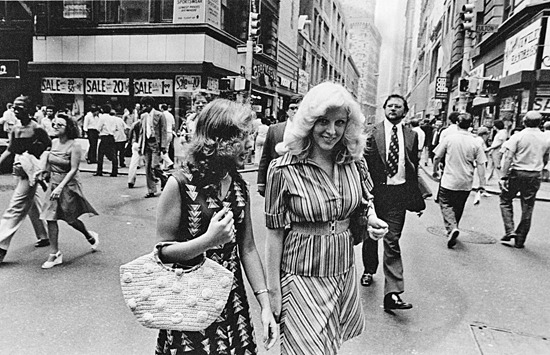

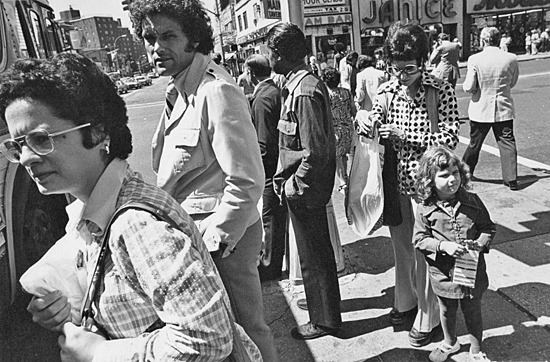

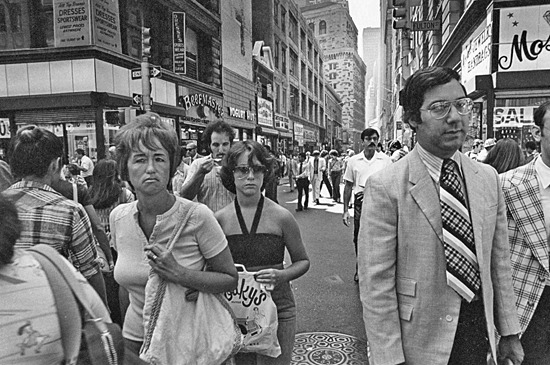

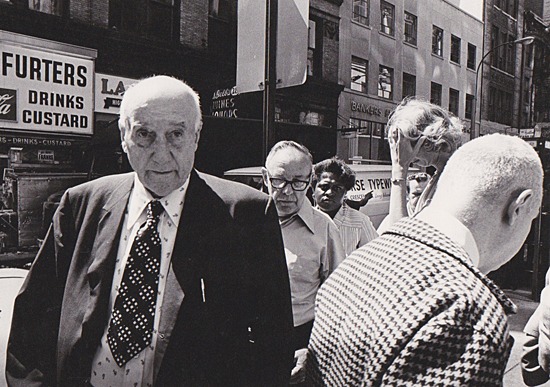

Winogrand’s photos showed an amazing lack of adherance to any rules of composition. Like the streets below, the images were filled with people in motion. There was a precarious, dynamic balance between humor and loneliness in the odd angles–an unfamiliar but powerful combination.

Winogrand’s perplexing teaching style

We looked at the portfolio without hearing a word of explanation. Winogrand spoke little. He seemed bored and restless, uncomfortable about being stuck in a classroom. When he did talk, his raspy voice reminded me of a a New York cabdriver’s. A few times, people tried breaking the awkward silence with a question that was answered with barely a monosyllable. We had a coffee break. Winogrand still wasn’t talking. He seemed to be waiting for us to ask him to tell us something, but whatever he had to say wouldn’t come easily. We struggled to find questions, hoping one would coax some information out of him. Winogrand broke one long silence by telling an off-color joke. We went home after four hours, perplexed. What had we learned?

The next day, Tuesday, was a bit better–the questions came faster, there were fewer silences–But ultimately just as perplexing. Winogrand told us that anything was photographable. He said that we only make the pictures we know; it is hard to break from our preconceptions about how something should look photographed. He told us to let what we see determine where the edges of the photograph go. He challenged us to forget our preconceptions about how to photograph something. “A photograph,” he said, “is the illusion of a literal description of how the camera saw a piece of time and space.” I wanted to know what technique Winogrand used to get his best shots, and all he’d talk about was a strange, esoteric theory!

By Wednesday, the students were getting restless. We had a gripe session with the program director; several students were ready to drop out. The direcor confided that Winogrand doesn’t make learning easy; be patient, he earged, it’s worth it. If we weren’t satisfied by the weekend, he’d give us a refund.

The breakthrough!

Back to class. After an hour or so of Winogrand’s interminable jokes and more coffee, the whole exercise seemed futile. Suddenly, almost in exasperation, he said, “Aww, let’s go out and take some pictures.”

That’s when the class started.

He opened his camera bag. In it were two Leica M4’s, equipped with 28mm lenses, and dozens of rolls of Tri-X. The top of the bag was covered with yellow tabs. He told us he wrote light conditions on the tabs and put them on rolls as he finished them so he would know how to develop them.

As we walked out of the building, he wrapped the Leica’s leather strap around his hand, checked the light, quickly adjusted the shutter speed and f/stop. He looked ready to pounce. We stepped outside and he was on.

We quickly learned Winogrand’s technique–he walked slowly or stood in the middle of pedestrian traffic as people went by. He shot prolifically. I watched him walk a short block and shoot an entire roll without breaking stride. As he reloaded, I asked him if he felt bad about missing pictures when he reloaded. “No,” he replied, “there are no pictures when I reload.” He was constantly looking around, and often would see a situation on the other side of a busy intersection. Ignoring traffic, he would run across the street to get the picture.

Incredibly, people didn’t react when he photographed them. It surprised me because Winogrand made no effort to hide the fact that he was standing in their way, taking their pictures. Very few really noticed; no one seemed annoyed. Winogrand was caught up with the energy of his subjects, and was constantly smiling or nodding at people as he shot. It was as if his camera was secondary and his main purpose was to communicate and make quick but personal contact with people as they walked by. At the same time, as he passed from shadow into sunlight into shadow again, he was constantly adjusting his meterless camera. It was second nature to him. In fact, his first comment right out the door was, “nice light–1/250 second at f/8.”

I tried to mimic Winogrand’s shooting technique. I went up to people, took their pictures, smiled, nodded, just like the master. Nobody complained; a few smiled back! I tried shooting without looking through the viewfinder, but when Winogrand saw this, he sternly told me never to shoot without looking. “You’ll lose control over your framing,” he warned. I couldn’t believe he had time to look in his viewfinder, and watched him closely. Indeed, Winogrand always looked in the viewfinder at the moment he shot. It was only for a split second, but I could see him adjust his camera’s position slightly and quickly focus before he pressed the shutter release. He was precise, fast, in control.

Inspired, I shot eight rolls that day. Up all night printing, the next morining I excitedly showed Winogrand some 50 workprints. He divided them up into a good and a bad pile, then handed them to me without comment. I pressed him for details: what made this print work? Why did he like that shot? He simply said, “It’s a good photograph.” He told me to take a close look at the shots he liked and keep shooting. I was disappointed, but I felt challenged.

Shooting like a maniac, printing all night

The rest of the workshop followed the same pattern. I shot like a maniac all day (as did most of the other students), worked in the darkroom until dawn, schlepped my pile of 8x10s back into New York from Long Island for the 9 a.m. class. Winogrand divided the shots into good and bad. I studied his selections, trying to divine his logic. I eventually realized that when the whole photograph worked–an intuitive response to something visual, unexplainable in words–he liked it. If only part of the photo worked, it wasn’t good enough. Cropping was out–he told us to shoot full-frame so the “quality of the visual problem is improved.” Winogrand told us to photograph what we linked, and to trust our choices, even if nobody else agreed with them.

By the second week, Winogrand had opened up and told us about his working methods, which were rather unorthodox but not sloppy. He never developed film right after shooting it. He deliberately waited a year or two, so he would have virtually no memory of the act of taking an individual photograph. This, he claimed made it easier for him to approach his contact sheets more critically. “If I was in a good mood when I was shooting one day, then developed the film right away,” he told us, I might choose a picture becuase I remember how good I felt when I took it, not necessarily because it was a great shot. You make better choices if you approach your contact sheets cold, separating the editing from the picture taking as much as possible.”

Winogrand developed by inspection to avoid overly contrasty or flat negativves. He would make contacts, then make 8×10 prints of everything but technically inferior negs. “I need to see what they look like large before I can make selections,” he explained. To save time, he exposed the negatives in bulk–a hundred or so 8×10 or 11×14 prints at a time. As he finished one exposure, he put the print in a box and exposed the next negative. When he was done, he would develop the prints en masse. These were workprints, so quality was not expected to be the best. Exhibit prints, however, had to be perfect. “Without technique, you won’t get anything good,” he noted.

Winogrand found some of his best-known themes by looking through his workprints. He never went out saying “I want to photograph X today,” because this would create preconceptions and prevent him from being open to seeing other things. He worked with no preconceptions about what would be a proper photographic subject or how a photo should look. He said, “I photograph something to see what it will look like photographed.”

Winogrand encouraged us to look at great photographs. See prints in galleries and museums to know what good prints look like. Work. Winogrand recommended looking at The Americans by Robert Frank, American Images by Walker Evans, Robert Adams’ work and the photographs of Lee Friedlander, Paul Strand, Brassai, Andre Kertesz, Weegee and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He told us to place ourselves where a lot is happening to get a lot of pictures. His favorite place to shoot: Columbus Circle in New York City, Sundays at 3 p.m. (“Lots of action.”) Why did he tilt his horizons? “What tilt?” he answered. He wasn’t interested in keeping the horizin straight within the frame, but always had a vertical frame of reference in his images. (This may be the only rule of composition he taught us.) He told us to treat editing photographs as “an adventure in seeing” and to enjoy the whole process. He said that tension between the form and content of a photograph makes it succeed. He told us that the most successful art is almost on the verge of failure.

These random ideas eventually added up a coherent approach to photography that can be summed up in two words: no preconceptions. His photos looked like nothing that came before. Even his teaching method (letting the students create the lesson by responding only to their questions) reflected his philosophy of not relying on any previous example of how it’s done.

After two weeks, exhausted, I saw my camera and the world differently. Encouraged by Winogrand’s parting words–“Get another camera and work at it”–I bought a Leica M-3 with a 35mm Summaron and continued exploring.

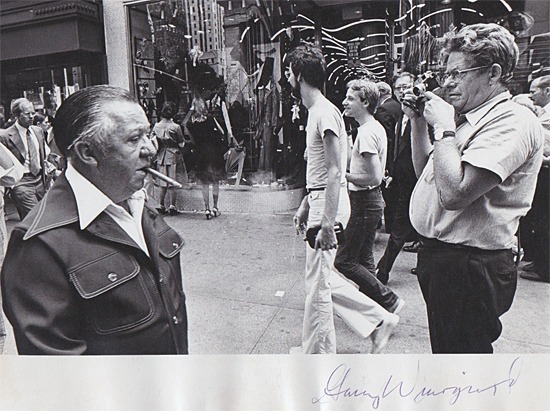

I saw Winogrand only once after that workshop, at a lecture he gave at my alma mater, Queens College, in 1982. I showed him some recent work. He said he liked it, and told me to keep shooting. He signed a photo I took of him at the workshop and said, “See you next time.” But there wasn’t a next time. Two years later he was gone.

Photo © 1976 by Mason Resnick

Garry Winogrand died of cancer at age 56 in 1984 and left over 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film, 6,500 rolls of processed film, 3,000 rolls of contact sheets that evidently hadn’t been looked at–a total of 12,000 rolls, or 432,000 photos Winogrand took but never saw. Some of these images were published posthumously in Figments from The Real World and Garry Winogrand (published in conjunction with the retrospective show at SFMOMA–the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art).

The above article originally appeared in the June 1988 issue of Modern Photography. It was written by Mason Resnick, who was the associate editor of Modern at the time. NOTE: This article has been reproduced on several other web sites over the years. This is the original source, posted by the author. Accompanying images may not be copied or reposted without the author’s permission.